The double edge of compounding

Compounding fuels wealth creation, but unmanaged costs can erode it.

People often underestimate the incredible power that compounding interest can have on wealth creation. Compound interest is the concept of earning interest on interest, thus resulting in your money growing at an exponential rate. In other words, not only do you earn returns on the money you invested, but also on all the interest you've accumulated so far, thus accelerating the growth.

When it comes to investing in the stock market, something similar happens. Stocks don't pay a fixed interest, but some of them pay a dividend. Reinvesting those dividends can have the same effect as compounding interest. Not all of them pay a dividend; they usually reinvest those profits to grow and expand the business, and you perceive that compound growth through the price of the stock rising over time, namely capital gains. Neither dividends nor capital gains are guaranteed; your investment could just as well nose-dive into the ground. Broad diversification by investing in a basket of stocks, or ideally the market as a whole, reduces these risks and, over long horizons, can smooth out volatility, aiding the compounding process.

Whether it's compound interest or compound growth, time is the factor that allows this phenomenon to emerge. It doesn't require any additional labor or sweat on your end; all it requires is patience and the mental fortitude of staying invested both when things are going well and especially when they aren't.

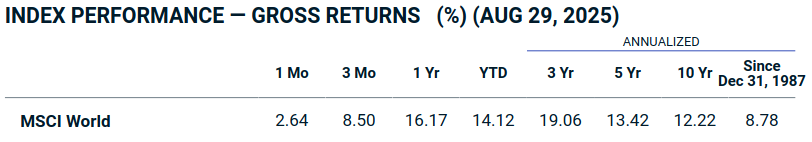

Consider the MSCI World index, which aims to track the performance of large and mid-cap stocks, around 1500 of them, across 23 developed countries worldwide.

Since its creation in 1987, it has achieved an average annualized gross return of 8.78%. Assuming an average inflation rate of 3-4% over that period, the real returns were roughly 5%. It doesn't mean that every year your investment in a MSCI World fund would have given you 5% returns; sometimes it might have been up 20%, other times down 30%, but on average over that period, that's how much you'd expect. Now let's play with compound growth.

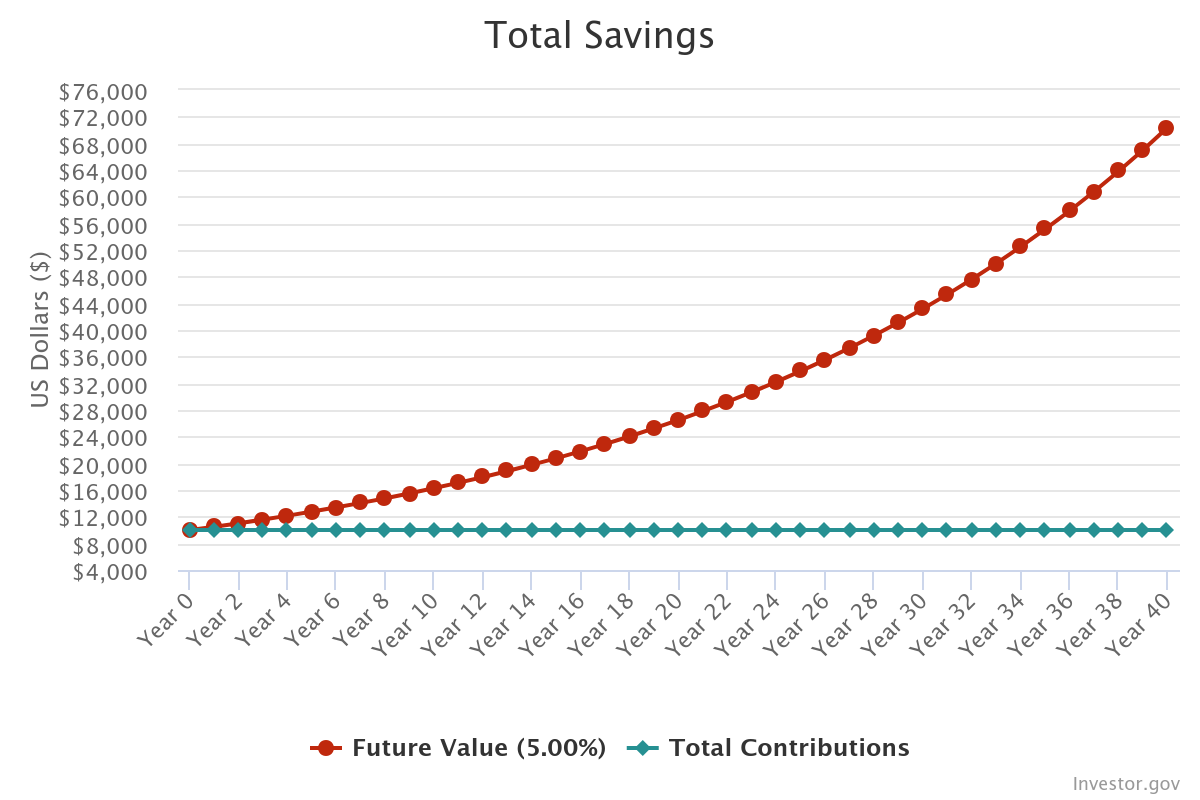

Let's say you invest $10'000 in the market just once, and then for 40 years you forget about it. With that one-time effort, your pot grows to a little over $70'000. You didn't have to work for it; the market worked for you.

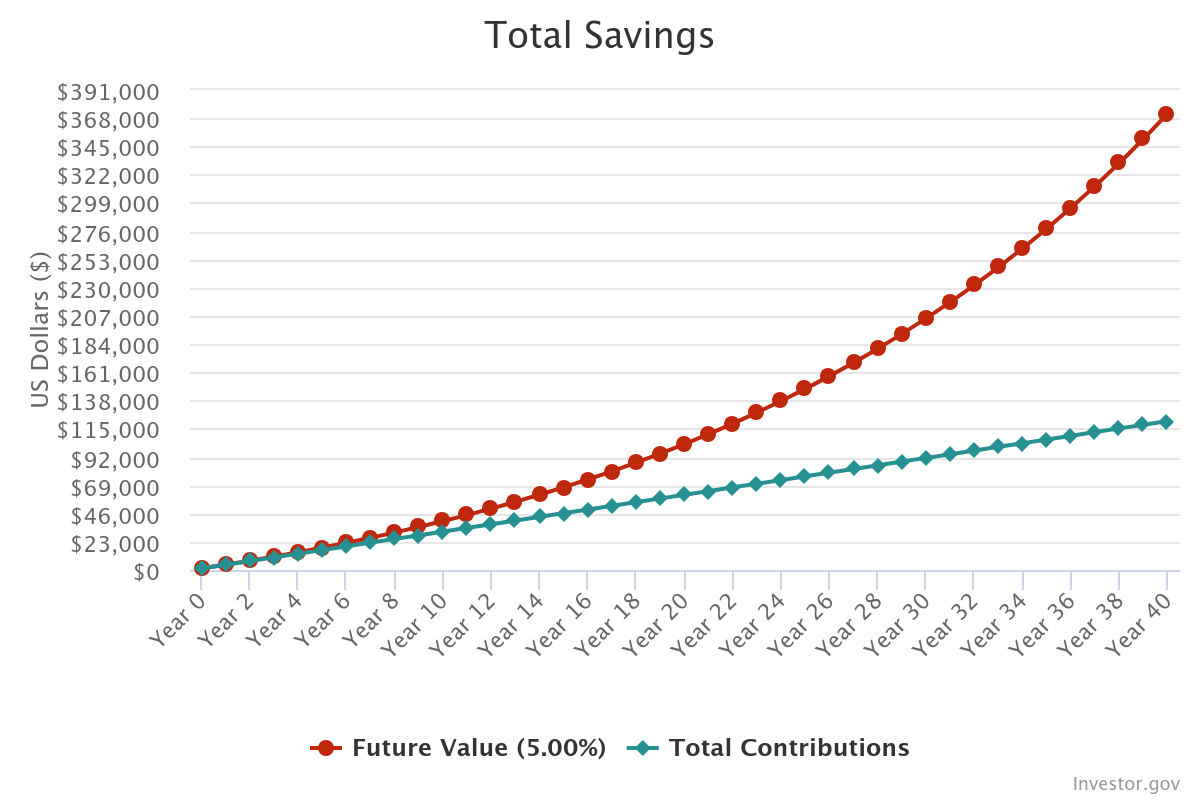

Now let's consider a more realistic scenario, where you make an effort. You don't have $10'000 lying around, so you start from nothing, but you commit to invest $250 every month. Now the pot grows to $372'000, and you only contributed $120'000 yourself over that time.

So compounding is quite useful. Unfortunately, this doesn't tell the whole story, because there are costs associated with investing, and fees matter a lot. When you decide to invest, you are essentially faced with two options:

- Invest yourself in a low-cost fund that aims to capture the market return.

- Invest in a more expensive active fund, where the fund manager claims to be able to beat the market.

Whether active investors can really beat the market is a hot topic. There has been much research on the matter, and it will be worthwhile to do a deep-dive on the subject another time. For this publication, we'll just summarize the key points of that research, which says that:

- Some active managers do manage to beat the market.

- Managers who beat the market cannot do so consistently, meaning they rarely beat it repeatedly over long periods of time.

- When all is taken into consideration, the amount of overperformance (returns in excess of the market) is comparable to the fees associated with the strategy.

In other words, even when they do outperform the market, you as the investor do not reap the benefits of it, all excess profits are drained by the higher costs associated with investing in an active fund.

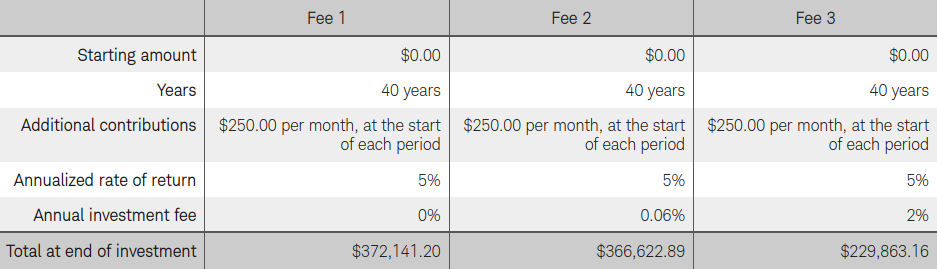

To put some numbers to it, nowadays it's fairly easy to find low-cost passive ETFs that track the MSCI World index, with annual fees in the 0.06-0.20% range. For actively managed funds, on the other hand, fees are typically in the range of 1-2%.

Consider once more the example where you invest $250 monthly, which means the first year you invest $3000. Using a rough approximation, the passive approach means paying around $1.8 in fees, whereas the costs would be around $60 for the active route (if 2%). It's an active fund after all, there's research and decisions to be made, strategies might change, events might occur, opportunities arise, and last but not least, the managers themselves need to be remunerated. It's no surprise the costs will be higher. I don't disagree, but here's the kicker: those are the costs you incur in the first year. Compounding works both ways. Just as compounding makes your investment grow exponentially, it also makes your costs grow at the same rate, and what appears to be a small difference early on grows to be difficult to ignore.

As the table shows, over those 40 years, you would not really obtain the full $372'000. With the low-cost passive fund (0.06%), you'd get $366'622, meaning you'd pay $5500 in fees over the full period. With the active strategy (2%), you'd obtain $229'863, meaning you'd pay a staggering $142'000 in fees. That's far from peanuts; you're leaving a lot of money on the table. Of course, this example assumes that the active fund manager failed to outperform the market and only returned the market premium (5%) which, historically, is far from being unreasonable.

The point I'm trying to make with this publication is not that active funds are inherently bad, but rather that expensive funds (active or passive alike) can eat a good chunk of your profits in an insidious way. Compounding over many years works in your favor when it comes to returns, but it also stabs you in the back when fees are concerned. So if you decide to invest in a high-cost ETF, or an active strategy that comes with an expensive price tag, you must do so only if you have reasons to believe that this approach will perform significantly above the market to justify the losses you will incur from the costs associated with it.

Read next

Lump sum investing vs Dollar cost averaging

Lump-sum investing often outperforms dollar-cost averaging; however, DCA remains popular due to behavioral factors like loss aversion and regret.

Home-country bias

Overweighting your home country in investments may feel natural, but history shows diversification is key to managing risk and volatility.

DEGIRO review 2025

DEGIRO is a low-cost brokerage platform available to European and Swiss investors. The article takes a closer look at what it has to offer.

SwissMisfortune

SwissMisfortune