Home-country bias

Overweighting your home country in investments may feel natural, but history shows diversification is key to managing risk and volatility.

It's a well-known phenomenon observed across the world: most investors tend to give too much weight to their own country's market in their portfolio. This behavior, often referred to as the home-country bias, certainly has understandable justifications, but it isn't without risk. In this article, we explore whether it's sensible to overweigh one's country.

By market capitalization, as of August 2025, Switzerland accounts for 2.5% of the MSCI World Index, and if we include emerging markets and instead look at the MSCI ACWI, the percentage drops to 2.1%. Although remarkable for such a small country, this does not change the fact that it represents only a tiny portion of the global market. According to a 2024 editorial piece by UBS, Swiss investors allocate 42% of their portfolios to Swiss stocks [1], which is nearly 20 times more. To call it a bias almost feels like an understatement, but Swiss investors are not alone; this phenomenon is seen all over the world. Let us explore the pros and cons of a home-country bias.

The good

Familiarity

They’re the names you see on the evening news, the companies your friends or neighbors might work for, the products you encounter daily at the supermarket or on your commute. Investing in local companies feels natural because, unlike distant foreign firms, you already have a sense of who they are and what they do. For a Swiss investor, that might mean Nestlé, Novartis, or UBS; household names that feel familiar and tangible. The performance of these firms often colors your perception of the broader economy: when their stock prices tumble, it can feel as if your own life is about to get harder; when they soar, optimism about the future tends to follow.

Tax advantages

Investing abroad often brings extra tax complications. Foreign governments typically withhold part of your dividends at the source, and while tax treaties may allow you to reclaim some or the totality of it, the process is not straightforward, and investors often end up losing a portion. By contrast, when you invest in your home market, these cross-border hurdles generally don’t apply. Instead, the main costs tend to be local charges such as stamp duty or transaction taxes, which are usually smaller and easier to navigate.

Currency risk

As we explored in a previous article on currency hedging, investing abroad does not just expose you to foreign companies, but also their currencies. A foreign market can deliver strong gains in local terms, but if the exchange rate moves against you, much of those profits can evaporate by the time they’re converted back into your own currency. Conversely, favorable exchange rates can sometimes boost your returns beyond what the market alone delivered. By contrast, investing in your home market avoids these fluctuations altogether: your assets, your dividends, and your spending remain aligned in the same currency.

The bad

Sector concentration

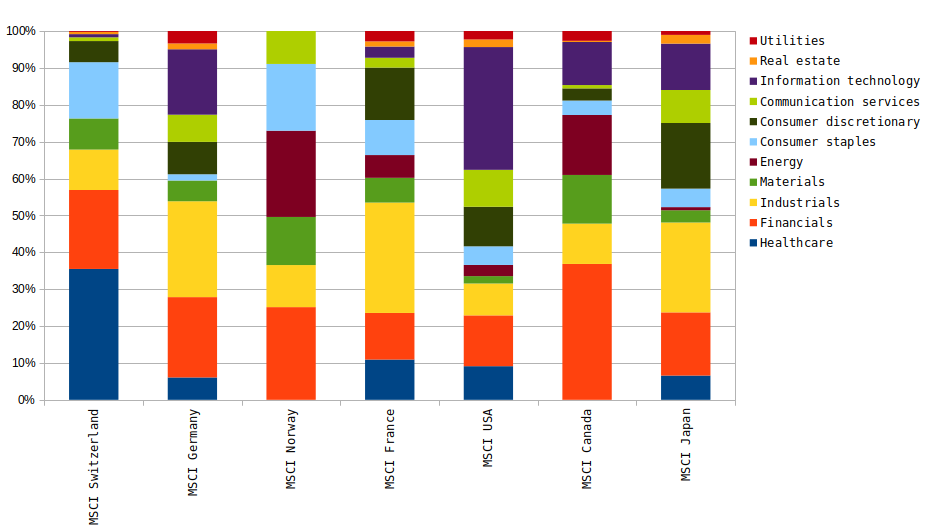

Not all countries are the same when it comes to economic structure. Some are rich in natural resources, while others excel in technology, manufacturing, or services. By concentrating your investments too heavily in a single country, you’re essentially placing an outsized bet on just a handful of sectors. Take Switzerland, for example, its stock market is dominated by financial and healthcare companies, which together make up more than half of the corresponding MSCI index. Other countries show similar patterns, Germany leans heavily on industrials, while Norway’s market is driven by energy and has little to no exposure to healthcare or information technology. These sector tilts are not inherently negative, but they do create vulnerabilities. Sectors move in cycles: during a pandemic, healthcare tends to thrive; during an energy crisis, oil exporters benefit disproportionately. A portfolio anchored too strongly to one country risks being overly tied to these cycles. In the long run, a heavy home-country bias can reduce resilience and make it harder to weather economic shifts.

Limited constituents

With a few exceptions, most national stock markets are built around a relatively small set of companies. The chart below illustrates the number of constituents for several markets using MSCI’s country-specific indices, which aim to cover about 85% of the investable equity universe in each market. That’s MSCI’s approach; other providers may use different methodologies. In Switzerland, for example, the MSCI Switzerland Index contains just over forty companies. By contrast, the Swiss Market Index (SMI), the benchmark most Swiss investors are familiar with, only tracks 20. For the sake of comparison, the MSCI World index tracks 1350 companies in developed countries and the MSCI ACWI 2500 worldwide. The difference is striking. Such concentration creates risks over the long term: when only a handful of companies dominate an index, the fortunes of a single firm can disproportionately affect the performance of the entire market. The collapse of Credit Suisse is a vivid reminder that even large, seemingly stable companies can falter or vanish, leaving investors exposed.

Volatility

The chart below comes from a 2021 Vanguard study, which examined market volatility across different countries from 1970 to 2020. Volatility refers to how much investment returns fluctuate over time, and it is often used as a proxy for risk: the more a market swings up and down, the bumpier the investor’s experience. The study shows that, in most cases, individual country markets are more volatile than the global market as a whole. The intuition is straightforward: national economies do not move in perfect sync. While one country may be going through a downturn, another might be enjoying strong growth. Holding both together helps smooth out the ride, as gains in one part of the world can offset losses in another. This is one of the core benefits of diversification. Overweighting your home country, by contrast, increases the likelihood that your portfolio will be closely tied to local turbulence and therefore subject to sharper swings.

![Volatility of returns by market [1]](https://www.swissmisfortune.com/content/images/2025/09/volatility.png)

The bias is bigger than you think

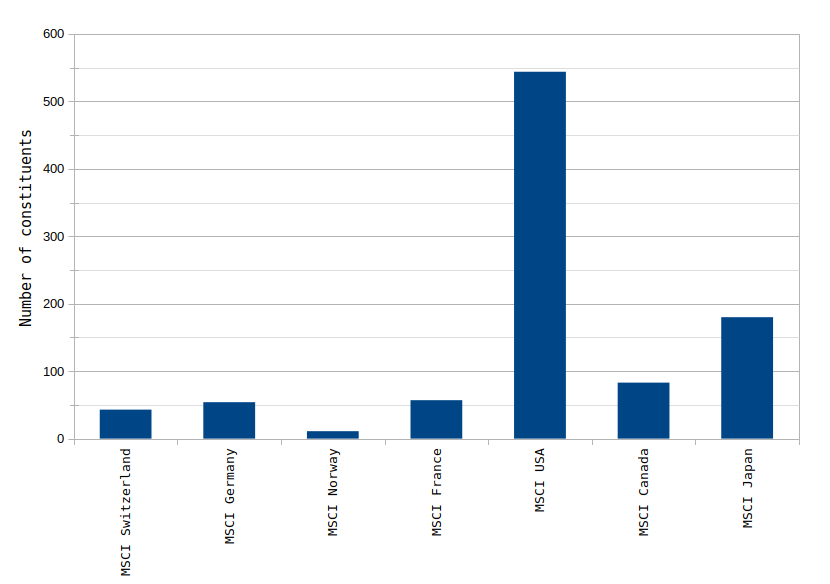

So far, the article has focused mostly on the stock market and how a home-country bias shows there. But in reality, your exposure to your home economy is often larger. If you work in Switzerland, much of your future income (your “human capital”) depends on the Swiss economy. If you own property, that too is tied to your country's real estate sector. Your pension contributions might also be invested heavily in the Swiss market, take for example, a third pillar fund by VIAC, specifically the global 100 variant that invests exclusively in stocks. As you can see from the composition, 39% is invested in the Swiss stock market through the SMI and SPI indexes. Although the exact fraction might vary based on your provider, the exposure is usually sizeable.

A similar consideration should be given to your 2nd pillar. Likewise, some life insurances also come with investment components, and those as well allocate a portion to the local market. In summary, it isn’t just about what you plan to invest in the future. Much of your existing wealth already carries home-country risk, sometimes more than you might expect.

How did Switzerland do

Over the past three decades, the Swiss Market Index (SMI) has held up reasonably well against the MSCI World Index. There were extended periods when Swiss equities outperformed, although in more recent years they have trailed global markets, with the performance gap steadily widening. For investors who maintained a strong home-country bias during that time, the results were far from disappointing. Thanks to the power of compounding, those early years of relative outperformance still leave many with cumulative returns that surpass what they might have achieved with a lower allocation to Swiss stocks back in 1996. That said, markets are far from predictable, past success offers no guarantee of future performance, but history can teach us something nonetheless.

Lessons from history

Over the past 15 years, the US stock market has experienced an extraordinary period of growth. The S&P 500 index, a benchmark for US equities, has achieved a compound annual growth rate of approximately 13.8%, or about 11.2% after adjusting for inflation.

Whether you are a US citizen or an international investor, it's easy to be tempted by such returns. Why invest in the global market or even the Swiss one when the American one has been on such a growth path? Fifteen years is a lot; it could continue to grow, or at the very least, it could continue to outperform the global market. Google, Microsoft, Apple. With such powerhouses, it almost feels difficult to imagine that such a market might eventually fall.

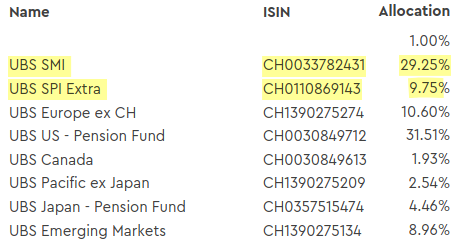

However, history serves as a prudent reminder of the inherent risks of market concentration. In the 1980s another country was at the top: Japan.

Japan’s recovery from World War II is widely regarded as an economic “miracle.” Despite occasional turbulence, the Japanese economy was booming in the late 1980s. A combination of stock market exuberance and skyrocketing real estate prices, Japan could boast some of the largest banks and corporations in the world. At its peak, the Japanese market was even larger than the US market, accounting for roughly 45% of global market capitalization, and it appeared destined for global economic dominance. You might guess what happened next: in the early 1990s, the economic bubble burst.

![Japanese stock market returns 1980-2024 [2]. Source: JustETF.](https://www.swissmisfortune.com/content/images/2025/09/japanese-stock-market-returns-1980-2024.png)

Not only did the market crash, but it took more than three decades for it to reach the same levels again. Thirty years is not far from the time horizon most investors have when planning for retirement. Through this lens, having a heavy home country bias could profoundly affect your long-term financial outcomes. While no one expects the worst-case scenario, even less drastic downturns can have a significant impact on your future wealth. It is essential to recognize that such risks are very real and should be considered when structuring your portfolio.

Conclusion

Although the tendency to overweight your home country in an investment portfolio is understandable, history reminds us that it can carry serious consequences. Losing your job during a domestic downturn is difficult enough, but if your investment portfolio is also heavily skewed toward the same country, the financial impact is effectively amplified.

For long-term financial resilience, it is crucial to be aware of the home-country exposure that already exists in your wealth, through employment, real estate, or pension contributions, and to adjust the allocation of future investments accordingly. Diversifying internationally can help smooth returns, reduce volatility, and better protect your portfolio against the inevitable ebbs and flows of individual economies.

Bibliography

[1] UBS Editorial Team, March 2024, Reduce home bias to improve your portfolio.

[2] Vanguard research, April 2021, Global equity investing: The benefits of diversification and sizing your allocation.

[3] https://www.justetf.com/en/academy/japan-stock-market-crash.html

Read next

Lump sum investing vs Dollar cost averaging

Lump-sum investing often outperforms dollar-cost averaging; however, DCA remains popular due to behavioral factors like loss aversion and regret.

DEGIRO review 2025

DEGIRO is a low-cost brokerage platform available to European and Swiss investors. The article takes a closer look at what it has to offer.

Factor investing: the capital asset pricing model

The CAPM was the first framework that tried to explain how an asset’s risk affects expected returns and laid the foundation for factor investing.

SwissMisfortune

SwissMisfortune